There’s a thrilling moment in a Manhattan art gallery captured in a six-minute video on YouTube when Jerry Saltz, Pulitzer Prize-winning art critic for New York magazine, declares that New Zealand artist Susan Te Kahurangi King (Ngāti Hauā) is a genius, and announces in a quite loud and very confident

voice: “You don’t need her backstory. That’s a fallacy.”

He is at once absolutely correct and completely wrong. He means the work – in particular her fantastical, intensely detailed, deeply moving figurative drawings in pencil and ballpoint pen, made when King was a teenager and in her 20s, closed off from the world in an IHC sheltered workshop on Auckland’s North Shore, mute since she was 4 years old growing up in Te Aroha – needs only to be looked at, no biographical information necessary.

True, the work is amazing. King’s art is exhibited across the US (New York, Miami, Philadelphia) and Europe (Paris, Düsseldorf). She is one of only three New Zealand artists held at MoMA (the Museum of Modern Art) in New York.

Te Papa acquired six of her drawings, currently on display in Wellington; she is also part of a group show at Robert Heald Gallery, also in Wellington, and other works are about to be exhibited at a show in Lexington, Kentucky. All of it, like nothing anyone has ever seen, so original and bewildering that the artist she is most likened to is Picasso.

But to think only of the work is to perform the act that has afflicted or shaped her whole life – of ignoring her. King has an autism spectrum disorder. She was born in 1951. She was a chatty little girl, the second eldest of 12 in a very Christian household, but stopped talking at about 4, her grandmother and fierce advocate Myrtle recording every overheard word (“tiki”, “Māori doll”) in the years that followed. One of the last things she said was after a funeral. She came home and said, “Dead. Dead. Dead.”

She attended school for a year but was told not to come back; there are heartbreaking letters at the time from her teacher wondering if she was deaf, which is a pretty good summary of the level of understanding of her condition. She was examined by a Dr Fox, who observed, stupidly, “An obviously backward child with a vacant face.”

The family moved to Auckland. She was sent to Northcote’s Kingswood IHC school. Teacher’s report on her first day, August 3, 1960: “Dripping wet after being saved from drowning the day her family shifted.” She did not belong there. She absolutely did not belong to the institution she was sent to in a year that keeps coming up in stories about her life, a year always said with an ominous tone: 1965.

She was 13. She went to the infamous Ward 10 at Auckland Hospital: the psych ward. They tried to force her to talk. It was primitive therapy at best and no one really knows what it was like at worst. Her drawings from that time are nightmarish.

I heard the stories from her sister Petita Cole, who showed me many of King’s drawings – beautiful, funny, dark, with repetitive images of Donald Duck set among sharp-clawed creatures with forked tongues, drawn on letterhead and scraps of paper, often crouching in the right-hand corner with the rest of the page blank. I didn’t know whether to cry or try to reason with it, make sense of it. The former was easy and the latter was impossible.

I noticed a very similar response from artist Stuart Shepherd when he was filmed seeing her work for the first time in Dan Salmon’s touching 2012 documentary portrait, Pictures of Susan. Shepherd broke down in tears. Salmon wanted to take something Shepherd had said and include it in the film’s trailer: “She’s our Picasso.” It was pulled out at the request of the New Zealand Film Commission. They felt it was absurd, ridiculous. Salmon was later very happy to be told that one of her works was exhibited next to a Picasso at a show in Europe.

Present yet absent

The first question I asked Cole at her Auckland home was, “Is Susan here?” In fact she lives with another sister, Wendy, in Hamilton. I was at Cole’s house for six hours and it felt increasingly weird to be talking for so long about King without her being anywhere in the vicinity – it was as though it wasn’t important for her to be there, to materialise.

Guiltily, I thought: ‘what difference would it have made if she had been there? Who can talk to a mute?’ Interviews are made of language. It was as though she were a ghost within the machine of Salmon’s documentary, too – a silent, peripheral presence who walked with a stoop and one hand held behind her back, her face impassive, no eye contact with anyone, straightening tea towels on the oven door, a little and distant woman of impenetrable mysteries.

The longer I stayed at Cole’s house, the more I felt I was being watched by the person who wasn’t there. It was unnerving to inquire about this singular and unknowable artist who cannot speak for herself. She had no art education of any kind, and yet “a very senior New Zealand artist”, according to her gallerist Robert Heald, came up to him at the recent Aotearoa Art Fair and said: “She is definitely our best artist.”

Another journalist, Laura Preston, has gone the extra air miles to get to know her: she flew out from the US to spend 10 days with King and her family, travelling to look at her childhood home in Te Aroha as well as make an observational inspection of Rangitoto Island (King got lost there once, causing a huge drama – how do you find someone who doesn’t speak?). The longform profile will be published in The New Yorker.

The closest I came to a sense of her was being shown the spare bedroom where she sleeps in Auckland – the stuffed toys, the little single bed – and, of course, when I saw the drawings, which I looked at in a daze. King had been an avid reader of comics as a child – the pictures, not the words; there is no evidence she can read.

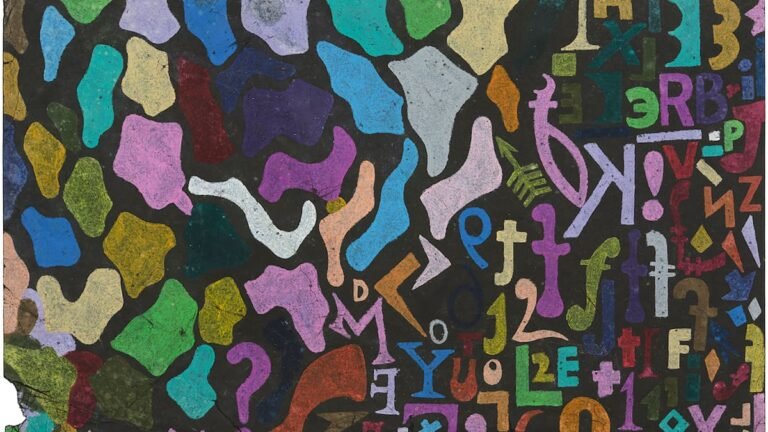

Her many drawings of Donald Duck, Mickey Mouse, Bugs Bunny and other characters are sometimes grotesques, and sometimes patterned with letters that read backwards. There is the immediacy of graphite and the vivid surprise of pastels. Always, her line is sure, and deliberate. She never erases. Her art begins with the first mark and unfolds from there. And so I suppose I was engaging with the essential sense of her. Heald held to the Jerry Saltz view, that her art was all that mattered.

“I think there is a risk of reducing the work to the biography, that her story and her neurodivergence can kind of eclipse the actual work,” he said. “When you look at the work, it’s self-evidently excellent and speaks for and of itself … Artists have always recognised how good the work is because there’s a purity to it.”

I asked painter Dick Frizzell. He finds her work bewitching: “Visually, the work more or less follows all the recognised rules of formal contrast, but on the other hand it doesn’t. It kind of gets there by a completely original route.”

I asked abstractionist Paul Hartigan. He described her as “a monumental practitioner”, and added, “King is deeply moving in that William Blake kind of way – a lone soul in the midst of maelstrom and wonderment.”

Whanganui painter Andrew McLeod, in an interview in 2021 about his favourite works of art that he’s bought over the years, nominated a Susan King drawing from the dark years after 1965: “There’s amazing mark-making and compositional skills there that leave me stunned and humbled … She’s the most complex and inspiring artist alive in New Zealand.”

But all the fine appreciation somehow just falls away, and Jerry Saltz’s dictum vanishes, at any small sign of a life lived. Who we are is more important than what we do. King likes going on drives, walks to the park and outings to the shops, said Cole. She will put on her coat and wait to be noticed, or not wait: to make her intentions clear, she will breathe heavily.

Grandma Myrtle’s diary, May 3, 1956: “Hysteria best part of the day, didn’t want shoes on or face washed or hair done and jumping on and off things all day and banging herself on the head and laughing. Asleep 9.30pm.”

Families and feuds

Interesting family. King’s parents met in 1947 at New Zealand’s first Māori language school; father Doug went on to teach te reo in colleges and at Mt Eden Prison (King’s work has made repeated use of koru and other Māori motifs), while mother Dawn became a homeopath. The 12 children include Rachel King, who performed in the 1986 touring production of The Rocky Horror Show alongside Russell Crowe and Rob Muldoon. Cole, born nine years after Susan, has become her property manager, creating a brilliantly cross-referenced catalogue to record a vast number of drawings.

But her role has caused a family rift. The tensions are clear in Salmon’s 2012 documentary. “That’s a debate I tried really hard to stay out of,” said the film-maker. Pictures of Susan also marks the last stand of Australian curator Peter Fay, who helped discover King and exhibited her in Sydney for the first time. I called him at his home in Hobart.

He said Rachel introduced him to her sister’s work on her phone; dazzled, he flew to Auckland at his own expense, and his first sighting of her work in real life is captured in the documentary. He was knocked out, judiciously so; he found her very early work “boring”, and her more recent work “like colouring-in”. The work in between struck him almost blind. “I felt like I’d stumbled in and suddenly found Picasso,” he told me. “It was sensational, extraordinary … She’s the real thing. A true artist. There’s no doubt about it. She’s got a vision of the world that she follows and it’s just pure raw talent.”

There is a risk of reducing the work to the biography, that her story and neurodivergence can eclipse the work.

He’s shown in the film telling the family they ought to get her work into museums and galleries, but is met with considerable resistance. He said from Hobart, “I thought there were some absolute masterpieces among them. My advice was, ‘You’ve got this enormous body of work here and it should be represented in both New Zealand galleries and around the world.’ Because at this stage the work was under beds and in cupboards. And I said, ‘That’s not respecting her work.’ From about that point on, I sort of became persona non grata. My relationship just sort of drifted away and that was that.”

He had no idea Cole had stepped in and that the work was now in collections around the world. “I’m pleased about that,” he said. He has fond memories of King at the show he curated in Sydney in 2009, shyly peeping at people looking at her work with a smile on her face.

“There was definitely a recognition that she knew this was her work. That sort of ownership of it that she had was worth the whole experience.”

Asked if he had any other sense of her as a person, he said, “No, not much, really. I apologise for saying this, but she was a kind of blob. When I first met her, she just sat in her chair and didn’t move.”

Dan Salmon filmed her for four years. Towards the end, she shook his hand; the act reduced him to tears. When they first met, though, there was no eye contact, no engagement. “She was a heavy presence,” he said. “She would sit there, or straighten everything and if there was a single apple core in the scrap bin, she’d take it outside. Her brain was always fussing about details. But she relaxed when she started drawing.”

A return

The central uplifting drama of his film is that King had stopped drawing for years and became depressed, showing little interest in anything until Salmon, as Cole said, showed up in 2008 “and asked the pivotal question. He said, ‘Would she or could she ever draw again?’” Her last dated drawings were from 1992. Her mother Dawn recorded in her diary, “Her drawings were increasingly becoming repetitive and aimless with a real ‘nothingness’ about them.”

The family decided to act on Salmon’s question. They went about it in stealth and considerable cunning, slowly guiding her to pick up a pencil and resume making marks on paper.

“She had this sort of long silence,” said Salmon, not meaning to be ironic. “When I met her, she was shut down. But as she started drawing again, she opened up.” His film captures the excitement of her renaissance. Artfully, Salmon also films butterflies emerging from a chrysalis in the King family garden. “Hopefully, you know, the metaphor wasn’t overplayed in the film, but the butterfly coming out was genuinely how I felt watching her, that she was coming out of this long, long sleep.”

It’s a lovely story arc and King is clearly happier, re-energised, except her new drawings lack the force and artistry of old. If there are two Susan King art periods, Susan I before she stopped and Susan II after she returned, it’s the former that constitutes her apparent genius. It was the first few works in Susan II that Peter Fay dismissed as “colouring-in”, geometric patterns with heavy use of felt, not entirely absent of figures or motifs but often kind of bland.

Robert Heald acknowledges the key focus of overseas collectors is her work from the 60s and 70s. “I don’t think it’s unusual for artists to have a period of work which is favoured,” he said. “But I think the later work will remain important, particularly in context with the early work.”

I asked him for his absolute favourite drawing. He nominated a drawing of Auckland Harbour Bridge from the 1970s. He described her mid-70s work as “symphonic”, as “virtuoso performances”. I asked him, “Are you moved by her work?”

He said, “Absolutely. There’s this sense of things under tension – I ought to be careful of biographical readings here, but I get quite a strong sense of bodily entrapment or bodily frustration. All these figures gesticulating and kind of protesting.”

I think I was moved to tears by the way her drawings pull you into a totally unfamiliar world. You don’t know where you are or what you are looking at except that these strange marks came from the secret mind of Susan King, now 73, who spent much of her adult life making potato peelers for 50 cents in a sheltered workshop.

From her mum’s diary: “When on holiday at the beach, with a stick she would draw complicated figures in the sand, sometimes a hundred yards or so long.”

From the North Shore Times Advertiser, in a report by “a lady visitor” to the Northcote IHC on June 25, 1963: “I visited the room in which one of the junior groups was painting and was shown the artwork of a 12-year-old girl who had not uttered a single word since her parents moved to the North Shore three years ago. The drawings show a high degree of concentration and observation plus a tremendous amount of imagination and ability.”

Susan King, at 4 years old, from Grandma Myrtle’s diary, April 25, 1956: “Had been sick and not eating, was glad to get her black golliwog & her coloured pencils and began colouring.”

Six drawings by Susan Te Kahurangi King are on display in Mahi Rārangi | Line Work, a group show at Te Papa .