Despite the closures in recent years of several commercial galleries thanks to market woes and public institutions facing funding cuts, a growing number of privately funded, non-commercial galleries are breathing new life into London’s cultural landscape. This month sees the arrival of two new art spaces: Ibraaz and Yan Du Projects, both in Fitzrovia.

Ibraaz, funded by the Kamel Lazaar Foundation and run by Kamel Lazaar’s daughter Lina, occupies a grand, stone-fronted building that has been home to a hospital, a synagogue and a 19th-century clubhouse for German artists. Now, its six floors host a dedicated performance space, library, bookshop, café and, in the building’s cavernous hall, an exhibition space. Its programme is explicitly dedicated to highlighting what Lina Lazaar describes as “global majority” artists — those of African, Asian, indigenous, Latin American or mixed-heritage backgrounds.

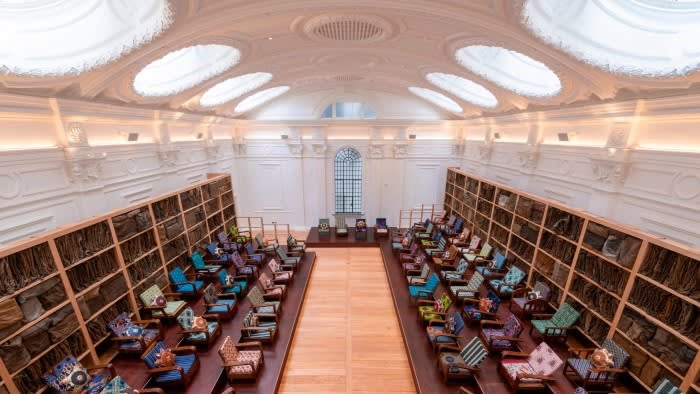

For its first exhibition, Ghanaian artist Ibrahim Mahama’s evolving interactive installation Parliament of Ghosts has turned the room into a political chamber replete with repurposed Ghanaian textiles. The space has been transformed, down to the floorboards, which are made of wood from Ghana’s railway stations. It’s an ambitious exhibition, and one that was no doubt costly to stage. Lazaar tells me that Ibraaz has signed a 15-year lease and is completely self-funded. “We’re extremely blessed in that sense,” she adds.

Around the corner in an 18th-century townhouse on Bedford Square, Yan Du Projects, funded and overseen by the eponymous art collector, comprises multiple floors for exhibitions as well as a studio for artists in residence. “We are very focused on supporting the artists who are overlooked by the art market, especially in an international context,” Du tells me, adding that the gallery will focus on the Asian diaspora. Its first exhibition will comprise three floors of paintings and sculptures by Duan Jianyu — a major painter in China who rarely shows outside of her home country.

Du wants the space to feel personal: “It’s homemaking for the artists, for the curators,” she tells me. “We are private, but we are welcoming.”

Privately funded art spaces in London have various purposes. The Brown Collection in Marylebone, opened in 2022 by Glenn Brown, is a more traditional private museum — one that displays his work (known for its appropriation of historical paintings) alongside old masters from the artist’s own collection. It’s a model that draws “visual connections between things”, Brown says. “Mark-making is very important.”

In contrast, Du’s private collection of more than 500 works, including by Yayoi Kusama, Georgia O’Keeffe and Louise Bourgeois, won’t appear in her new space, whose goal she says is to instead “advocate for communities and ecosystems”.

Alexander Petalas, who founded The Perimeter in 2018, started with weekly, appointment-only tours of his collection of contemporary art, which includes work by Wolfgang Tillmans and Sarah Lucas. Now, he hosts a year-round exhibition programme anchored by artists in the collection, and plans to expand his Bloomsbury space. “It’s grown into something that feels a bit unstoppable,” he says.

As Georgina Adam, author of The Rise and Rise of the Private Art Museum, explains, “a lot of [these spaces] shy away from the word ‘museum’.” But their activities — programming free-to-visit exhibitions with no sales mandate — make them a natural comparison.

A key difference is that their funding decisions are in the hands of their owners whereas, in the public sector, institutions are regularly forced to adapt in order to avoid unpredictable shortfalls. Tate, for example, has continued shedding staff since the pandemic, having reported a deficit budget for 2024-25 thanks to a reduction in paying visitors from abroad.

“There aren’t as many restrictions and logistical and administrative hoops we need to jump through in order to stage exhibitions that we think are interesting,” Petalas says. Though they tend to have advisory boards, decisions about what happens in these places often come down to the person funding them. “I trust myself,” says Du, “I know what I’m doing.”

Wigmore Hall, the classical music venue in London, recently decided to stop accepting public funding. Its director John Gilhooly cited the administrative requirements of Arts Council England’s Let’s Create strategy, which aims to broaden access to the arts, as a key reason, telling the BBC that “the current policy is just too onerous”.

And in America, worries about government steering public arts institutions are growing as Donald Trump escalates his campaign to purge the Smithsonian of “divisive or ideologically driven language”, ordering a review of its programming and operations such that it reflects “the unity, progress, and enduring values that define the American story”.

Cultural funding is conditional, and most of it is fragile. In avoiding the public sector’s compromises and the assumptions that governments aren’t themselves subject to ideological over-reach, privately run spaces can better embody their owners’ singular visions. At Ibraaz, Lazaar tells me, “the resources really serve the vision, and not the other way around”.

From October 14, ydp.co

From October 15, ibraaz.org

Find out about our latest stories first — follow FT Weekend on Instagram, Bluesky and X, and sign up to receive the FT Weekend newsletter every Saturday morning