‘I just don’t like eggs!’ is an unusual title for an art exhibition. It is a quote taken from an English art collector, Janet de Botton, and used by artist Andrea Fraser in her seminal performance work ‘May I Help You’ (1991), which is currently echoing throughout the galleries of Fondazione Antonio dalle Nogare, in Bolzano, northern Italy, reverberating with questions that cut to the core of the art market’s inner workings.

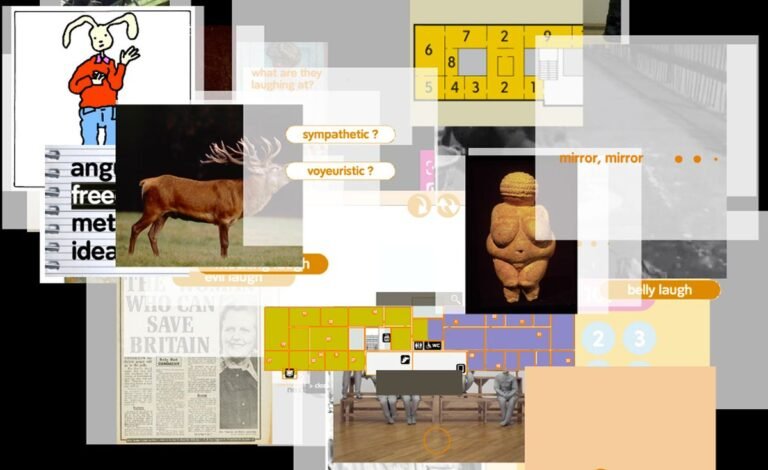

The retrospective brings together Fraser’s works made since the 1980s, focused on her research on art collectors, collecting and collections, broadly encompassing her archival impulse and investigations in psychoanalysis and sexuality, made approachable through her humorous lens.

Andrea Fraser, ‘I just don’t like eggs!’ at Fondazione Antonio dalle Nogare

Walking up to Fondazione Antonio dalle Nogare, an eco-brutalist space built by architect Walter Angonese on a picturesque hillside, the sound of muttered words and heavy doors slamming resonates throughout the courtyard. ‘I spent a few hours recording in a cell block,’ Fraser explains. CCI Tehachapi at King’s Road (2014) is a sound installation recorded at the California Correctional Institution Tehachapi, a maximum security prison. Fraser intended to draw parallels and contradictions between freedom and confinement, between sets of society that tend to not intersect: ‘These are extremes in society, between economic divisions, racial divisions, geographical divisions.’ Index II (2014) is a graph overlaid onto the entry window, its bars reflective of confinement, ‘visualising the parallels between prison construction, museum construction, wealth concentration and incarceration in the United States’.

‘Who are these people in art galleries? Where do they get their money from?’

Andrea Fraser

Andrea Fraser, Jeff Preiss, Orchard Document: May I Help You?, 1991/2005/2006 (film still), Film 16mm (color, sound) transferred to high-definition video (loop). Production: ORCHARD and Epoch Films

(Image credit: Courtesy of the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery)

Fondazione Antonio dalle Nogare serves not only as a public exhibition space and a repository for the eponymous founder’s collection, but also as a residence, where artworks coalesce with daily life. ‘The artworks circulating within these spaces serve as an interesting context for the exhibition,’ Fraser observes. It is in this intersection between private and public that her interests lie. Since the 1980s, Fraser has been analysing the workings of art marketing, peeling back its layers to question hierarchies and positions of power that in turn affect what is displayed in a museum. Four iterations of May I Help You play on loop, in which Fraser or actors perform monologues that oscillate between the veneer of salesmanship and alienation. ‘Culture is ordinary, culture is common,’ she explains. ‘Who are these people in art galleries, where do they get their money from?’ This question is at the crux of the exhibition: who decides what can be considered as an object of cultural value?

Antonio dalle Nogare describes Fraser’s approach: ‘The artist’s sociological and psychoanalytic approach becomes the lens for questioning the art world and highlighting its contradictions, projections, wills, and wishes.’ Fondazione Antonio dalle Nogare itself illustrates the impact of collectors on the establishment of a museum, where personal taste and financial backing determine what is exhibited; all collections have a different focus or goal.

The exhibition begins with an installation titled Aren’t they lovely? (1992), exploring the mechanisms through which value is assigned and preserved within museum settings. A series of objects, including coins, medals, eyeglasses, photographs and souvenirs, a bequest of Therese Bonney, are on display in glass cabinets. Fraser found over 100 other objects from Bonney’s home in storage at the museum; Bonney had donated her entire collection to the University of California, Berkeley, but these objects remained uninventoried. The wall texts are museum curator notes, revealing the criteria applied to objects deemed worthy of being an artwork. ‘The wall texts are the most radical thing I’ve ever been allowed to do in a museum,’ Fraser explains. By reintroducing domestic culture and objects of only personal value alongside the works legitimised by museums into a public space, the artist short-circuits the value system proposed by the institution itself.

Andrea Fraser, Um Monumento às Fantasias Descartadas, 2003 (A Monument to Discarded Fantasies), mixed media (Brazilian carnival costumes). Exhibition view, New Orleans’ international art festival, Prospect.3, 2014-2015

(Image credit: Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Nagel Draxler Berlin – Cologne – Munich)

‘The idea that someone supported Trump and was on the board of a museum was quite frustrating to me’

Andrea Fraser

Other works explore issues of plutocracy within art institutions. 2016 in Museums, Money, and Politics (2018) is a vinyl installation of pie chart analysis and breakdown examining the relationships between politics and art institutions in the United States of America. ‘The work started with the realisation that I had in 2016 whilst at MOCA (Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles) at their Annual Gala. One of the members of the board told me that he had just become Trump’s campaign finance chair. The idea that someone supported Trump and was on the board of a museum was quite frustrating to me.’

Fraser researched 128 art museums, one from each federal state, during 2016 (the year Trump was elected), documenting the contributions to political parties or groups made by the boards of directors. ‘Board members are not necessarily patrons, however, they technically are because to be on a board you have to make personal financial contributions. These individuals are paying to play.’ The work highlights the undemocratic state of public institutions in the US, where those with expendable wealth are able to buy their way into roles of governance. In turn, museums and culture become saturated towards supporting certain groups or ideas over others.

Installation view of ‘I just don’t like eggs’

(Image credit: Courtesy of the artist an the gallery)

‘I just don’t like eggs!’ underscores the stark disparities between social groups, their priorities and freedoms, exposing the harsh realities of governance by the wealthy. These findings prompt pressing questions: Who wields authority over what defines art? How are museum displays curated? What dictates the value of art? Why are certain pieces prioritised over others? Who reigns supreme – artist, museum, or collector? And what forces drive shifts in the art market? As Fraser’s insights linger, these inquiries demand urgent exploration.

Andrea Fraser retrospective ‘I just don’t like eggs’ at Fondazione Antonio dalle Nogare until 22 February 2025