![Banner [Virtual] Art Gallery Banner [Virtual] Art Gallery](https://baystatebanner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/GlorettaBaynes5-1024x660.jpg)

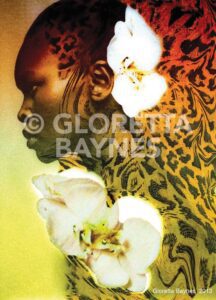

“Nina Simone Ascension” by Gloretta Baynes

Banner [Virtual] Art Gallery

Sponsored by City of Boston | Mayor Michelle Wu

This is the 14th interview in a weekly series presenting highlights of conversations between leading Black visual artists in New England. In this week’s installment, artist James Perry talks to artist Gloretta Baynes. The interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Gloretta Baynes is a Cambridge native and an alumna of the Massachusetts College of Art and Design. She works in airbrush, pen & ink, pencil, fabric, collage, mixed media and digital photography. As a curator for Violence Transformed, she continues her life’s journey as an artist/storyteller, sharing her personal creative/spiritual explorations and advocating civil rights and social justice within the context of her work. Baynes’ work is in the collections of the Dei Foundation & Art Alliance, Ghana; the Oyasaf Foundation, Nigeria; the Museum of the National Center of Afro-American Artists; the Association of African American Museums; and private collectors.

James Perry: Gloretta, tell us a little bit about yourself and how you got started.

Gloretta Baynes: Amazingly enough, I talked to my mom years ago. She told me I started drawing when I was 3. My father did some drawing, so I think I got some of my talent from him. I’ve always been interested in art, and I’m blessed to have family members who’ve been supportive of me.

Where did it go from there? When did you start saying ‘Alright, now I’m going to start doing this’?

Maybe when I was in grammar school. I was fortunate enough to go to the Morse [Elementary] School, which was interesting because they had a lot of different types of art. One of the things I remember in the first or second grade is walking down the hallway and seeing these beautiful mosaics of birds, and the colors were so vibrant, blues and purples. They really show up in my work. I realize that at an early age I was exposed to quality art in my educational environment.

When you were growing up, were there certain artists you looked up to or who inspired you?

Being in Cambridge, there was a pretty vibrant Black community. We had a Black people’s library. There were a lot of radical, progressive Black folks there. There were a few artists as well who lived in my immediate community. Being a young American artist who’s pretty fearless, I would actually see them at the library or see them exhibiting in the community, and they lived down the street. I would just go down the street and knock on their door and say, “Hi. I’m Gloretta and I saw some of your artwork.” They would kind of chuckle and let me in.

One of my colleagues, Dennis Didley, [aka] Vusumuzi Maduna, did a lot of charcoal drawings. His girlfriend also did charcoal drawings. He did sculpture. He would let me come over to visit and see what they’re both doing. This was right down the street from my house. So I was always in that environment where they would just nudge me along. Having people who were interested in what I was doing helped a lot.

How did your transition into high school affect your art?

I had an interesting art teacher named Ms. Winbush. She did actually every type of art in her art class. It was almost like a mini-Mass Art. She would try all these different types of mediums — ink, watercolors, acrylics, sketching, conte crayons. She embraced me and encouraged me to do my work. … I asked could I take an extra art class instead of going to study hall. So I ended up taking two extra art classes instead of two study halls. That’s how committed I was to exploring art.

Talk to us a little bit about your palette and the message you’re trying to convey — your form of art.

I usually work in blues and purples, something that’s very tranquil, soothing and relaxing. I’ve been told that when people come through the gallery, they respond emotionally to certain kinds of works. It’s that calming effect or that tranquility. It’s an experience where they can just step outside themselves, and when they come and see my work, they’re in a different place and in a safe space.

What would you say to young people of color who are talented to keep them going?

Reach out to artists in the community, because it’s not like the MFA where you go and you don’t know the artist. You see their work, but you can’t interact with them. You can’t have a dialogue with them, and you can’t ask them about the process. That’s the wonderful thing about being here with AAMARP. We’re able to work with the community. We’re able to mentor young people when they come in and have those conversations. They’re in a safe space where they can do that.

How important is it to have a mentor?

I think it’s very important because you need to have somebody who you can bounce things off of. They can kind of guide you through the process or just be a friend and give you an opinion, or gently guide you in a different direction — expose you to different types of things that ordinarily wouldn’t be available to you.

![Banner [Virtual] Art Gallery – The Bay State Banner](https://finance-pro.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/GlorettaBaynes5-768x495.jpg)