Few people can lay claim to irrevocably changing the world of photography like Cecil Beaton did. A true multi-hyphenate – an Oscar-winning costume and stage designer, illustrator, photographer and socialite – Beaton’s influence spanned magazine, screen and stage and also garnered a starry clientele, ranging from Marilyn Monroe and Audrey Hepburn to the British Royal Family and Coco Chanel. In the mid-19th century, anyone who was anyone wanted to be photographed by Beaton – but why? “There is no skull beneath the skin with Beaton – he is not trying to make some sort of psychological statement about the real ‘you’,” explains Robin Muir, photographic historian and Vogue contributor. “It’s all about the surface. It’s about the joy of photography.”

Muir would know. Having spent years delving into the Beaton archives, Muir has curated the Cecil Beaton’s Fashionable World exhibition which opens today (9 October 2025) at the National Portrait Gallery (NPG). Slated as the first retrospective to exclusively explore Beaton’s pioneering contributions to fashion photography, he says: “It’s really the first show anywhere to focus on the core of Beaton’s career and the discipline that gave him his earlier success, and that is fashion photography and the years that found him at his very, very best.

“A bit like Lee Miller or Lloyd Webber, people can’t get enough of their oeuvre, but these are [often] all-encompassing retrospectives providing a broad brushstroke outline of his various accomplishments: portraiture, fashion certainly, interiors, gardens, war photography, his service to the royal family, his trips to Hollywood. But this is the first time any show has focused on his fashion work and the fashionable people who came into his orbit.”

It is not NPG’s first foray into the world of Beaton. In fact, as Denise Vogelsang, director of audiences, reminds us, Beaton himself collaborated with the gallery in 1968. “It really was a groundbreaking moment in the history of the gallery,” she says. “It was the first NPG exhibition devoted to a photographer, the first time living sitters had been exhibited in an exhibition, the first show to exhibit non-British sitters, and the first solo survey accorded any living photographer in any national museum in Britain. It’s very exciting and fitting to see Beaton’s portraits on our walls once more.”

So, what’s new? This current exhibition spotlights his contribution to the evolution of fashion photography, which is often highlighted, but rarely examined in detail, and how his signature artistic style – a marriage of Edwardian stage glamour and the elegance of a new age – revitalised and revolutionised the game. Muir says: “The exhibition is from 1927 to 1956; in 1927, 23-year-old Cecil had come down from Cambridge without his degree and he’s been working in a very dispiriting office job in the city. When by luck, charm and sheer hard work, suddenly almost overnight, he becomes the star photographer at Vogue.”

His lifelong ambition of working for Vogue, however, stems from childhood. Born in 1904 in Hampstead, London, Beaton first got hold of a camera at the tender age of 12. “When he began taking photographs with a Box Brownie it was those closest to hand who became his first models, chiefly his very handsome – and endlessly patient – sisters, Nancy and Baba,” explains Muir. “He dresses them up and portrays them against increasingly exotic, homespun backdrops. He would often reference an early childhood memory as his introduction to both the allure of feminine beauty and the means by which to capture it.”

Peppered throughout the exhibition are pictures of his sisters, but also his mother Esther ‘Etty’ Beaton. She often posed for her son – although Beaton once said “she strongly objected in the middle of a busy morning, to being made to put on a full evening dress” – during which he cast her as the Madonna, The Virgin Mary, as he later did with the likes of Lady Lavery and Lady Diana Cooper too.

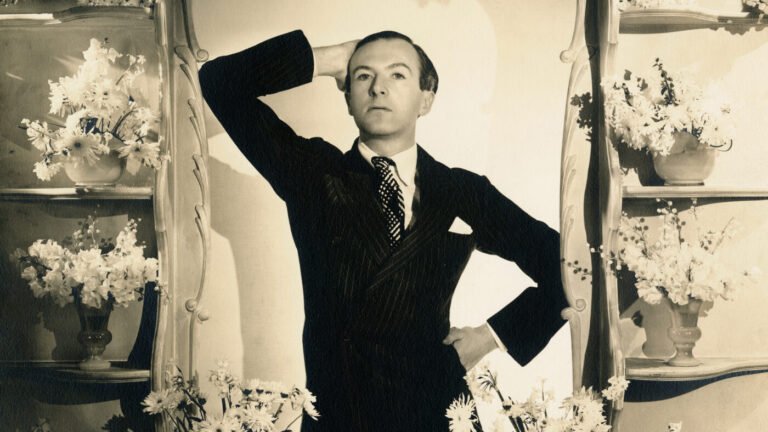

Atypical of the time, though, Beaton also made himself the subject of his photographs. Acquiring a 10-second timed shutter release for his camera kickstarted a lifelong practice of self-portraits, meaning he could also claim to be the inventor of the ‘selfie’. Often lauded as the world’s most photographed photographer, NPG alone has 360 portraits of Beaton, who often donned a woman’s wardrobe or historic uniform when in front of the lens. Beaton wrote in his diary as a schoolboy: “I don’t want people to know me as I am, but as I am trying and pretending to be” – and, ultimately, it was this experimentation with identity that underpinned his multi-faceted life.

Having studied art, history and architecture at Cambridge University – but eventually leaving without a degree in 1925 – he spent much of his twenties poring over Vogue. “He dreamt of Vogue. This is the man who once declared ‘when I die I want to go to Vogue’. After years of lobbying the magazine, his first picture was published there in spring 1924. Within three years he was hired by the magazine to make drawings and caricatures as well as photographs and, shortly after that, he was their chief portrait and fashion photographer.”

Muir says Beaton’s turning point came when he befriended some of London’s social elite. “Meeting Edith, Osbert and Sacheverell Sitwell, the leading avant-gardists of literary London in 1926, who took him under their wing. After coming down from Cambridge, Beaton was unsure about what to do next, where to take his photography or indeed if photography would work for him at all.

“Confiding this to a friend, Kyrle Leng, Leng said prophetically: ‘I would not bother too much about being anything in particular, just become a friend of the Sitwells and wait and see what happens.’ And this is exactly what happens: the three Sitwell siblings, the great polemicists of the time, become his earliest patrons and give him an entrée into a world he has only been able to observe from the sidelines.”

Soon, Beaton’s clientele expanded and he became synonymous with the Bright Young Things of the 1920s and 30s, capturing their flair for theatrics and costume. Impressed by his inventive use of backdrops and pose, Vogue signed him in 1927: a job that took him to Hollywood and Paris and saw him photograph Elizabeth Taylor, Fred Astaire, Francis Bacon and, inevitably, Julie Andrews and Audrey Hepburn. Muir adds: “The great thing about Beaton, especially when he started out, was that he was interested less in what his sitters were wearing but what they brought to the picture. Whoever ranged into his viewfinder, he wanted them to look the best they could possibly look at that moment. This could be achieved with what we might now call “styling’ but to him it was more about mood and ambience, the backdrop.”

Beaton’s first royal photographs appeared in 1939, when he was summoned to Buckingham Palace to take photographs of Queen Elizabeth, wife of the then reigning monarch George VI. Given he was the official wedding photographer for the abdicated Duke of Windsor and the twice-divorced Wallis Simpson in 1937, Beaton was deemed a bold choice. But his work put the royal family in a new light, capturing the Queen and then her daughters, Elizabeth and Margaret, as a modern, fashion-forward family.

“Though he professed technical incompetence, he used an amateur’s camera during his early years with Vogue and with extraordinary results,” says Muir. “In London, I would say he single-handedly turned fashion photography, if not into an art form then into something approaching art. And doing that while also being a remarkable polymath – he could turn his hand to almost anything, and was a man of varied and outstanding talents.”

However, it’s no secret that Beaton could be a difficult man to work with, regularly quarrelling with editors at Vogue and someone who wrote “venomous” diary entries about even his closest friends. His ties with American Vogue were abruptly severed in 1938 when an anti-semitic remark was published in one of his cartoons. Later, in 1955, British Vogue also declined to renew his contract after a slew of poorly-received stories and projects.

As the Second World War loomed, however, he was appointed an official war photographer by the Ministry of Information and his wartime service took him around the globe. This part of his portfolio is where many believe he is most skilled. “His documentary work on the realities of conflict and its aftermath, revealed him as a photographer of great compassion. As a lifelong cultural and social commentator his observations on taste, decoration and stylish living were eloquent; as a diarist he was often devastatingly forthright; as caricaturist his drawings were razor-sharp; and as an essayist he was witty and fluent on a range of subjects.”

The war’s end ushered in a new era of elegance and Beaton captured the high fashion brilliance of the 1950s in glorious technicolour, paving the way for what many deem to be his greatest achievement: the costumes and sets for the musical My Fair Lady, on stage and later on screen. “[The exhibition] ends in 1956 when, having been let go by Vogue on both sides of the Atlantic, Beaton turns his attention back to his first love: designing for the stage,” says Muir.

“He’s invited to create the costumes for a stage musical based on what he considers rather ‘unpromising material’ – George Bernard Shaw’s Pygmalion. That, of course, becomes My Fair Lady which ran for nearly 3,000 performances on Broadway and, when it opened in London in Drury Lane in 1958, it was the most expensive musical ever staged in the capital.

“When the film was suggested in 1963, where famously Julie Andrews loses the part of Eliza Doolittle to Audrey Hepburn, there’s little doubt about who will do the costumes and this time the set too.” However, Beaton found it an unhappy filming experience. One of his Oscars is displayed in the NPG exhibition, but it’s noted that he famously didn’t collect them on stage. Hepburn wrote to Beaton in 1965: “I wish you could have heard the applause.”

Now 45 years on from his death, Beaton’s work continues to inspire the world of fashion and his enduring influence can be felt among artists everywhere; case in point, NPG have just released a Beaton-inspired fashion collection with artist Luke Edward Hall, who has collaborated with Harriet Anstruther for corsages and Amelia Graham for silk scarves.

After meticulously researching Beaton’s every chapter, Muir says that despite his achievements, self-doubt never left him. “Among all this, it is surprising to learn from his diaries, published and unpublished, and that despite his polished public appearances and utterances, just how anxious and desperately insecure he could be about it all. He never really felt he belonged anywhere, having spent so long trying to rise up above a determinedly middle-class upbringing. I’m not sure if he ever worked out who he really was.”

Cecil Beaton’s Fashionable World is open at the National Portrait Gallery until 11 January 2026, visit npg.org.uk

Read more: Blue Lights’ Siân Brooke: “I never thought this was possible”