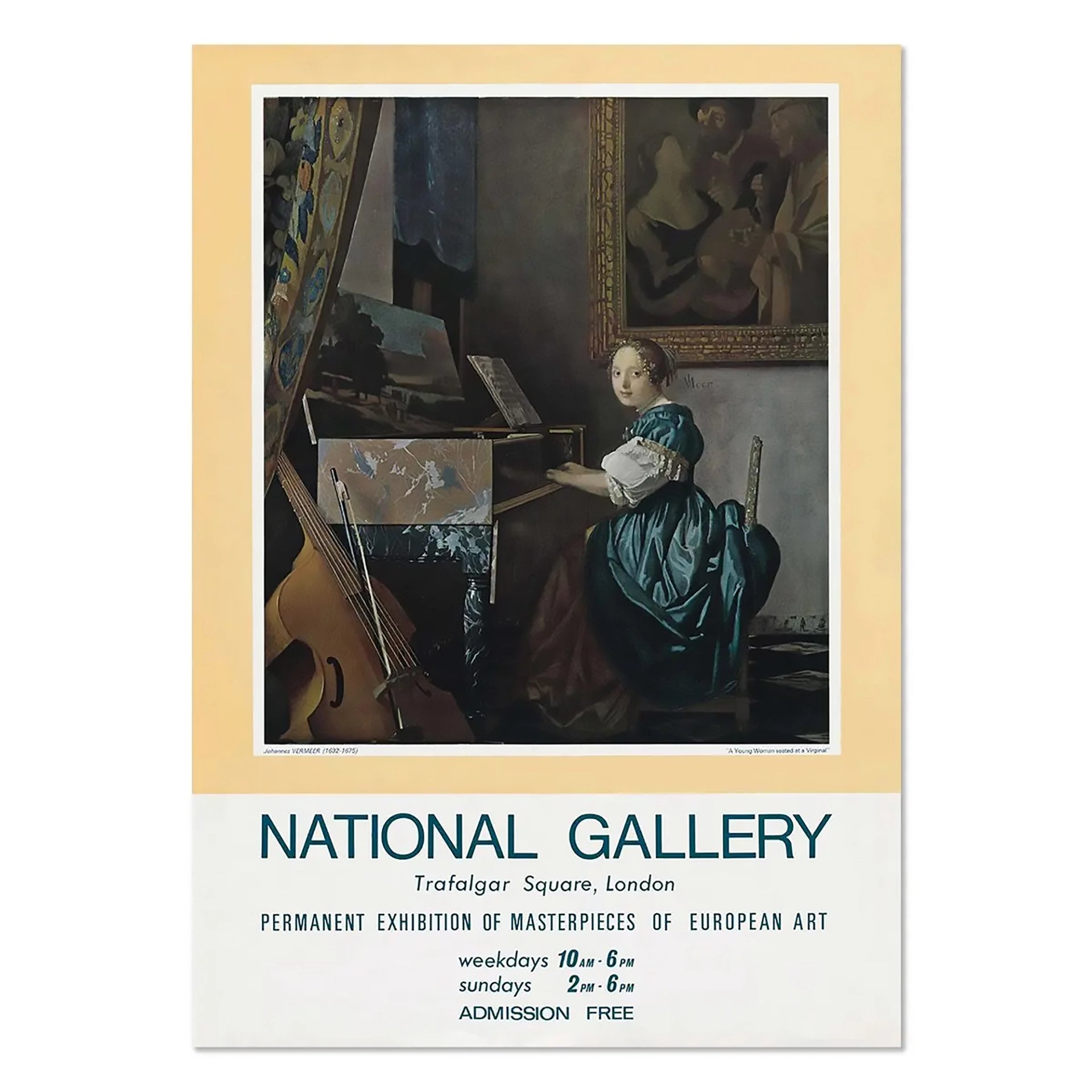

In 1968 Vermeer’s Young Woman Seated at a Virginal (1670-72) was vandalised at the National Gallery in London. No photographs were released at the time, but they have now been supplied to The Art Newspaper.

What makes this attack extremely disturbing is that the vandal attempted to completely remove the most important area of the composition: the head of the young woman.

As the then museum director, Martin Davies, told his trustees: “It seems probable that this was an attempt to cut out the head.” Had the vandal succeeded, they most likely would have stolen the circular canvas fragment (just over 10cm in diameter).

The damage was swiftly restored and is now virtually imperceptible; the painting is now protected with glazing National Gallery, London

The loss of the head would have been so catastrophic that it might well have been impossible to restore the painting in a meaningful way. Young Woman Seated at a Virginal would then have had to be taken off display permanently—effectively reducing Vermeer’s small surviving oeuvre.

The vandal at the National Gallery was never identified, since the attack was not observed and this was before recorded CCTV facilities were available. They were not caught and nothing at all is known about their motivation.

Young Woman Seated at a Virginal was at the time hanging in a Dutch cabinet room, on the National Gallery’s lower level (where Muriel’s Kitchen cafe is now located). The attendant was seated, but could only see ten of the 25 paintings, since they were displayed in bays.

On 22 March 1968 the room was opened at 10am, but not a single visitor entered until 11.15am. Just after 12pm a visitor saw the terrible damage, but assumed it had been reported and did not then mention it to the seated attendant.

By 1pm, an hour (and possibly nearly two hours) after the incident, none of the seated attendants had spotted the damaged Vermeer. It was only then that a visitor alerted staff. The Vermeer was quickly taken down and removed to the conservation studio.

In 1968 board minutes now opened up for The Art Newspaper, National Gallery trustees Andrew Forge and Veronica Wedgwood linked the attack to a poster campaign that featured the Vermeer painting National Gallery, London

That afternoon a short press statement was released after questions were raised by the Daily Express newspaper. A museum spokesperson said that “fortunately no canvas was removed and the paint loss is minimal”. This gave no idea of the extent of the damage—and how close it was to a complete disaster. The statement added that restoration would “present no grave problem”.

An examination of the painting revealed that a sharp instrument, probably a razor blade, had been used to cut around most of the woman’s head. For a quarter of the slashed line, the blade had fully penetrated the canvas, running between the eyes of the woman. The rest of the slashed line produced deep scratches, but the head was not removed. The Vermeer had been relined only three years earlier, and this extra thickness may have fortuitously made it more difficult for the vandal to penetrate the canvas. This represented a most unusual form of vandalism, but removing a key part of the canvas would have made it extremely difficult to “restore” the painting.

Davies reported to his trustees: “I was alarmed to notice that the attendant on duty, from his chair at one end of the room, could see only ten of the 25 pictures.” He added that “the small number of visitors that morning was a further disturbing factor; one important protection to the pictures is that plenty of visitors should be about in the rooms”.

After the attack, Davies favoured releasing a photograph of the damage—but he was overruled by the trustees. One of them, the artist Andrew Forge, thought it “wrong to publish…a photograph which might well excite the person who had committed the atrocity”. The sculptor Henry Moore, a fellow trustee, agreed, saying that it would “draw attention to the incident again”.

Forge linked the vandalism with the fact that Young Woman Seated at a Virginal “was now appearing on posters advertising the gallery”. Trustee Veronica Wedgwood, an historian, also believed the display of the poster in 200 tube and railway stations was connected.

Banned photograph

Edward Playfair, a former civil servant and trustee, suggested that the gallery should “allow any press representative to see the photograph who asked to do so, but that it should not in any circumstances be published”. This was agreed. It does not appear that any journalists submitted a request.

No photographs were released and there were only very brief news accounts in the press (the longest was just 130 words), based on the gallery’s statement. The incident went unrecorded in the gallery’s annual report. Since then, the damage has had virtually no coverage in the Vermeer literature. Arguably more publicity on the day of the incident might have encouraged a visitor to contact the gallery with valuable information.

Young Woman Seated at a Virginal was relined again, and the damaged area was retouched within days of the incident. It went back on display (in another room) on 11 April 1968, three weeks after the attack. Needless to say, the Vermeer was then protected with perspex.

The restoration proved very successful, and it is now virtually imperceptible when viewing the Vermeer under gallery lighting with its glazing.