In a sort of perplexing attempt at a gotcha story over at Fusion, Felix Salmon, (who memorably told the younger generation never to become a journalist last year, in a journalistic article) tells the tale of Sarah Meyohas, an artist who tried to essentially paint her stock trades and their effect on the market. It’s not her first artwork that looks at finance, value and the nature of investment.

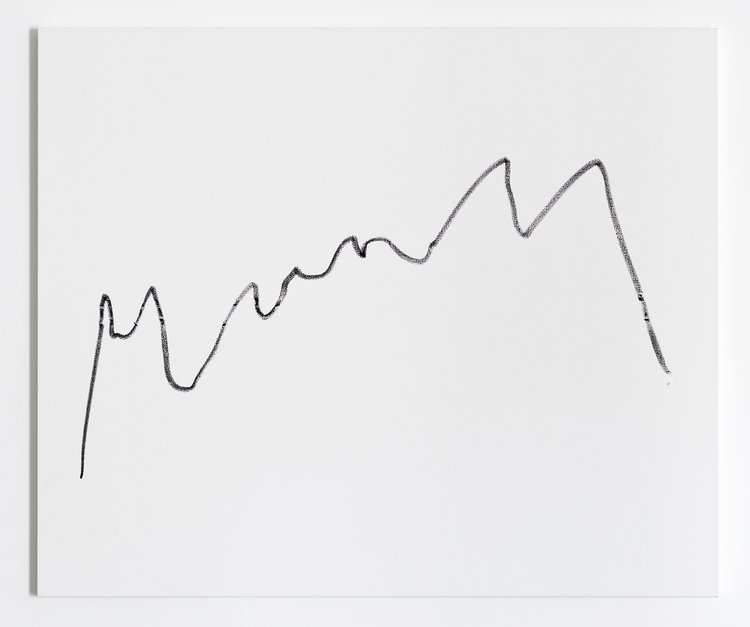

Last month, Ms. Meyohas reportedly sold stock from her Charles Schwab and TD Ameritrade accounts in front of a live audience at 303 Gallery, in Chelsea, as part of an art installation. She then painted as the stocks were affected, inspired by their fluctuations in value (she planned to lose money on this venture, though she didn’t say how much). The artist used only randomly selected stocks of firms with a market cap of under $40 million, according to Fortune‘s coverage of the event, so she’d have more likelihood of actually having an impact on the prices. Charles Schwab has since shut down her account, but won’t say exactly why.

The performance work was novel idea, and surely one meant to highlight how easily one can do what we assume Charles Schwab (who refused to comment repeatedly for Mr. Salmon’s story) now presumably accuses her of: manipulating the market. That’s a market that most of us rely on for our retirement, etc. so it’s pretty silly how easily it can be messed with. If you’ve lived inside a rock formation or just don’t pay any attention, see, for reference, high-frequency trading, collateralized debt obligations and that whole Enron thing that everyone has forgotten about.

Because they were small, relatively cheap stocks, it is entirely feasible that her trades did affect share prices. But did her art show affect share prices? Also, definitely possible. And that is why Charles Schwab was (understandably) worried, we’re guessing. The artist explicitly said she intended to “alter the prices of 12 different NYSE-traded stocks,” per Fortune. Yeah, that probably violates the terms of service of her brokerage account, and rightly so.

Of course, none of this is major money; it’s a technical illustration of how these things work, albeit in real time and for an audience, but not one that will have a real effect on the global stock trade or our economy. However, it does make you think: Is it that easy to inflate or deflate prices and should it be? Is a public art show public disclosure of information? Is having an Ameritrade account at all basically admitting that you are a n00b at capitalism and should just put your money in a sock under the bed? These are all fascinating questions (to some of us) and probably part of what Ms. Meyohas wanted us to ponder. But Charles Schwab, while perhaps interested in these questions, didn’t want to be the one posing them to a regulator.

So it’s kind of weird how Mr. Salmon takes a tone as though Charles Schwab, a financial institution regulated by a bevy of agencies, was being preposterous and mysterious to shut down an account that was being used to make a public spectacle of how easy it is to manipulate the market. “There was a clear artistic purpose in trading the stock,” he asserts, in the midst of an avalanche of indignant prose outlining how a company refused to comment to him on why they’d chosen to end their business relationship with a private citizen. Personally, I am heartened that Charles Schwab is so keen on privacy, but more important—who cares what the purpose of manipulating the market was? It’s still illegal. Is Charles Schwab supposed to be some kind of art benefactor? Has anyone asserted that “artistic purpose” is an exception to the law of the land? If it were, you can bet Lower Manhattan would suddenly be full of “artists.”

Indeed, if anything, the artwork and Charles Schwab, in discontinuing their services, are highlighting what a flimsy idea market manipulation is, which was, again, probably the point. As they say “on the Street,” it’s only called insider trading when you get caught. Otherwise, it is referred to as “good business.”