In a recent edition of Radio 4’s Desert Island Discs, the novelist William Boyd refers to the strange story of one of his most memorable creations – a biography of the artist Nat Tate that he wrote in 1998. Tate, an American abstract expressionist suffering from alcoholism, took his own life by jumping off the Staten Island ferry in 1960 at the age of 31, after destroying 99 per cent of his works.

Only after his death did the art world unite in praise of his talent.

The book Nat Tate: An American Artist 1928-1960 was a brilliant hoax, exposing many of the pretensions of the art world. Nat Tate, friend of Picasso and lover of Peggy Guggenheim, never existed, but news of Boyd’s biography was taken seriously, and art aficionados were quick to convince themselves they vaguely knew of, and certainly admired, Tate’s paintings.

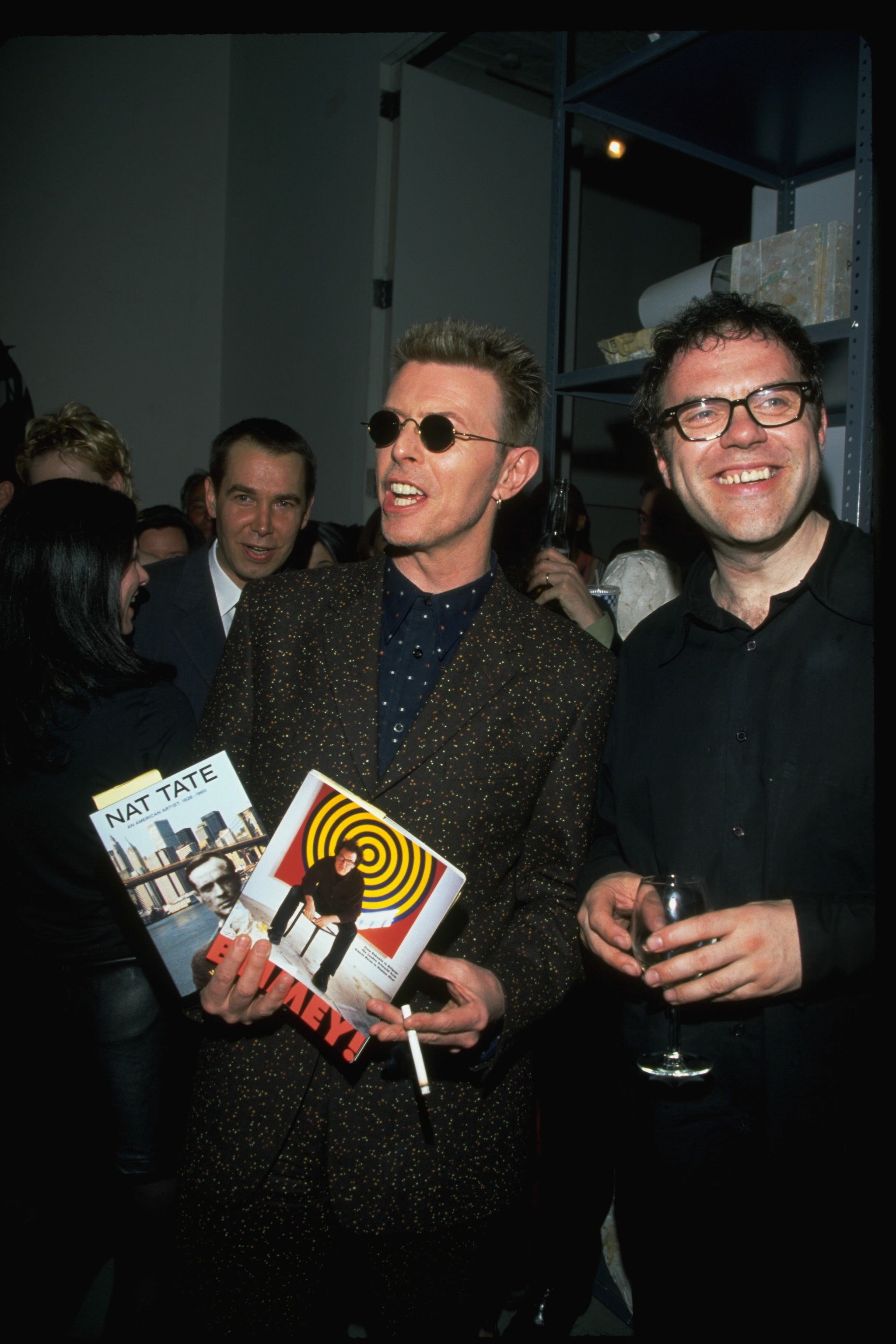

The fact that Nat Tate’s name was remarkably similar to London’s two most prestigious art galleries seemed not to occur to anyone. The book was launched at a glamorous party at the artist Jeff Koons’ New York studio. The party was hosted by David Bowie, whose publishing company had published the book.

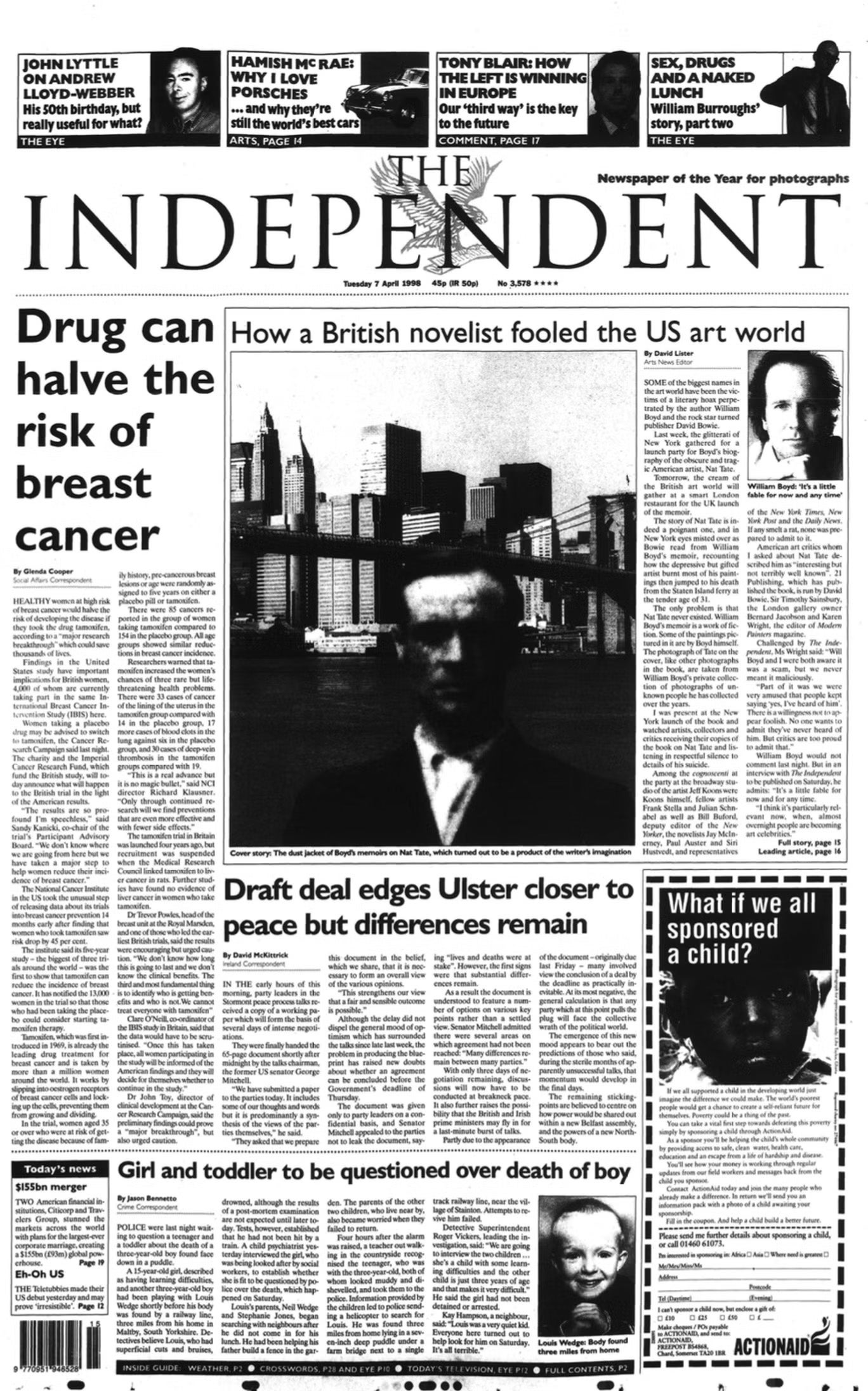

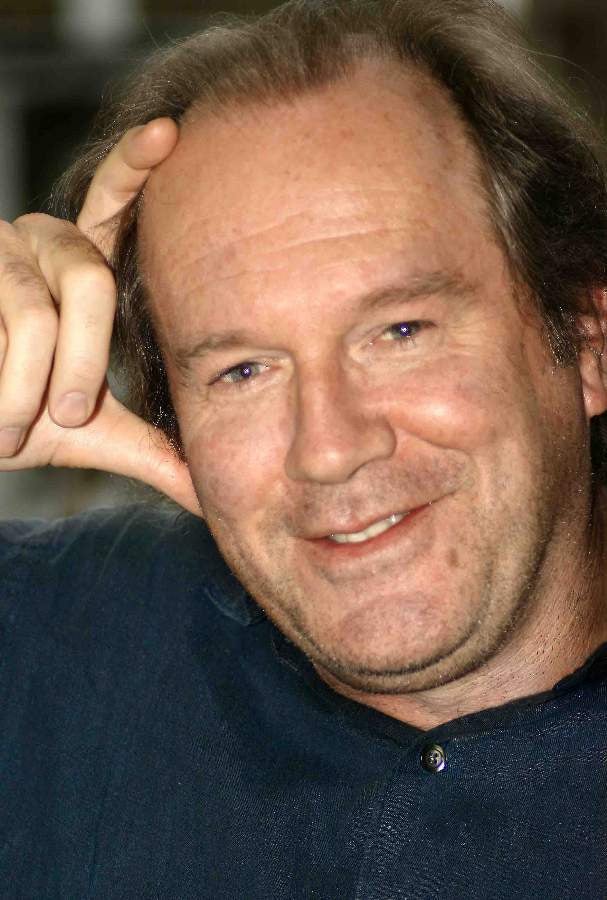

What could possibly go wrong? Well, as Boyd ruefully recalled on Desert Island Discs, “a British journalist” unmasked the hoax. I was that British journalist, unmasking the hoax for the front page of The Independent.

This is how it happened. I was The Independent’s arts correspondent at the time and was in New York for the launch, attending the bizarre party at Koons’s studio among the glitterati of the New York culture world. Guests included artists Frank Stella and Julian Schnabel, the New York novelist Jay McInerney, fellow writers Paul Auster and Siri Hustvedt, dealers, collectors, press and TV, and assorted rich hangers-on. The book itself had been endorsed with quotes from Gore Vidal and Picasso’s biographer John Richardson, both in on the hoax.

David Bowie, whom I was privileged to know and become friendly with during that decade, hosted the party in March 1998 with his supermodel wife Iman at his side. The room went silent when he read an extract from Boyd’s book. I knew that Bowie had the most infectious and delightful smile and chuckle, and certainly both were evident during his reading. I was at the front and fixed my gaze upon him, and he seemed to return it with his impish grin and twinkle in his eye.

The gathering had stopped sipping the whisky provided by the event’s sponsors as Bowie read (the musician, at the time, only drank water and sent an assistant to get some). The crowd took their eyes off Koons’s colourful, kitsch sculptures of kittens, and listened attentively, then resumed drinking, networking and seeing who could give the most knowledgeable opinions about Nat Tate’s life and work.

The project, of course, would have appealed to Bowie’s love of fantasy, acting a role, creating a persona, and indulging in sheer mischief.

I then started interviewing the great and good from the art world about Nat Tate. Sure enough, they said how they admired his work and though not hugely familiar with it, had always been dimly conscious of his status as an artist.

But while William Boyd on Desert Island Discs acknowledged that I did chat to the guests at the party, he didn’t explain what had first roused my suspicions that all was not as it seemed. A little bit of luck attends most scoops, and it was when I overheard an odd conversation among the organisers that piqued my curiosity to dig a little deeper. The chat seemed rather too knowing. I went back to my hotel room and re-read the short book and noted down the locations that had been apparently important in Nat Tate’s brief life. The next day, I trudged around Manhattan seeking them out.

I went to inquire about Tate’s life at Alice Singer’s 57th Street Gallery, where Boyd wrote that he had first seen one of Tate’s drawings. 57th Street indeed existed. Alice Singer’s gallery did not. Nor did any of the other galleries referred to in the book.

By the time I got to the launch party, I was fairly confident that something was awry.

Actually, Bowie himself had very nearly gone too far in writing on the jacket of the book that “William Boyd’s description of Tate’s working procedure is so vivid that it convinces me that the small oil I picked up on Prince Street, New York, in the late Sixties must indeed be one of the lost third panel triptychs. The great sadness of this quiet and moving monograph is that the artist’s most profound dread – that God will make you an artist but only a mediocre artist – did not in retrospect apply to Nat Tate.”

Neither Jeff Koons, who hosted the launch (held not insignificantly on the eve of April Fool’s Day), nor his fellow New York artists present were aware of the truth, or of the fact that at least one of the paintings in the book ascribed to Tate was by William Boyd himself. Photographs ostensibly of Tate were pictures taken by Boyd in various locations in the city.

As I wrote in The Independent at the time, “The critics, artists and gallery owners who have been taken in by one of the best literary scams in years must be wishing they could disappear as effectively as Nat Tate – and, like him, resurface with their reputations dramatically enhanced.”

William Boyd’s objective in writing his quite brilliant book was an intriguing and insightful one. Looking back, he has said: “My aim was, first of all, to prove how powerful and credible a pure fiction could be and, at the same time, to try to create a kind of modern fable about the art world. In 1998, we were at the height of the Young British Artists’ delirium. The air was full of Hirst and Emin, Lucas, Hume, Chapman, Harvey, Ofili, Quinn and Turk. My own feeling was that some of these artists – who were never out of the media and who were achieving record prices for their artworks – were, to put it bluntly, not very good.

“However, there was a kind of feeding frenzy going on, an art-driven South Sea Bubble or tulip fever, and the story of Nat Tate in this context was meant to be exemplary. What is it like to be a very average artist who achieves great fame and wealth?”

A few days after the launch, my exclusive appeared on the front page of The Independent. It was certainly the biggest scoop I ever had, going around the world. I was sent a cutting from a small paper in the Andes that revelled in the tale of Nat Tate and the subsequent unmasking.

I received a hug from my then editor at The Independent (well, it was the touchy-feely Nineties). William Boyd, though he seemed to recall the saga in tranquillity on Desert Island Discs, was not best pleased at the time. Understandably, he was unhappy that his hoax was unmasked before the British launch of the book. I went to that launch in London, and it was, let’s say, somewhat subdued and low-key.

Even now, all these years later, the saga can rear its head in unexpected ways, and not just with Boyd’s Desert Island Discs recollections. In 2011, a painting by Nat Tate titled Bridge no 114 (in fact painted by Boyd) was auctioned at Sotheby’s and bought for £7,250 by TV’s Anthony McPartlin. More recently, I came across a Wikipedia entry about the Nat Tate book, which quoted the American magazine Newsweek saying that I too, like Nat Tate, did not exist.

I’ll keep clear of the Staten Island ferry.