What does it mean to be an American artist or poet? In recent years, I have seen two group shows focusing on artist communities that addressed this question, both at the Grey Art Gallery (now the Grey Art Museum). The first was Semina Culture: Wallace Berman & His Circle in 2007, curated by Michael Duncan and Kristine McKenna. Centering on the nine issues of Berman’s avant-garde magazine, Semina (1957–64), the curators brought together work by a diverse group of mostly West Coast artists and poets who had published in it (John Altoon, Joan Brown, Bruce Conner, and others). Duncan and McKenna reminded viewers that this loosely affiliated, anti-establishment group represented a viable alternative to the dominance of the New York art world and the rise of Pop art and Minimalism, and what many saw as the commercialization of art.

The second exhibition was the Inventing Downtown: Artist-Run Galleries in New York City, 1952–1965 in 2017, curated by Melissa Rachleff, which focused on 14 artist-run and co-operative galleries. Like Semina Culture, this show homed in on a diverse community of artists who sustained each other in the face of the art world’s inhospitality. As Grey Art Museum director Lynn Gumpert and independent curator Debra Bricker Balken walked through Rachleff’s extensive, eye-opening show, and the different communities it presented, they began thinking about all the American artists who had moved to Paris after World War II, and how many returned and became central figures in the downtown New York scene. What about the others? Where did they go, and why?

Bricker Balken and Gumpert responded by curating the landmark exhibition Americans in Paris: Artists Working in Postwar France, 1946–1962, at the Grey Art Museum. As Gumpert writes in the foreword to the exhibition’s indispensable catalogue:

Digging deeper and deeper, we were astonished to find that there had been no major show or publication addressing this topic. What had inspired so many American artists to take up residence [in Paris] in the late 1940s and the ’50s?

While there is no single answer to this question, James Baldwin does put it into perspective. Gumpert notes, “According to Baldwin, in a piece he wrote for the magazine Partisan Review: [it was] from the vantage point of Europe [that the American] discovers his own country.” Baldwin left the United States because of racism, which was institutionally authorized and deeply embedded in American culture. We learn from the catalogue that others left for similar and equally distressing reasons.

The first works to catch my attention were the sculptures of Shinkichi Tajiri. Sadly, I was not surprised to learn that after serving with the 442 Regimental Combat Team and receiving the Purple Heart for valor in WWII, he was “subjected to relentless discrimination” at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and relocated to Paris in 1948, never returning to the US. Later he settled in the Netherlands, where he had a successful career.

Welded together from iron wire and machine parts, Tajiri’s “Wounded Knee” (1953) is the first modern sculpture to reference the deadliest sanctioned mass shooting in American history, when US Army troops massacred nearly 300 Lakota men, women, and children. The work, which Tajiri made “to purge himself of the horrors of war” resembles an abstract sentinel, whose hollow, porous outer body evokes an armored warrior unable to protect himself. The artist was friends with the African-American sculptor Harold Cousins, and taught him to weld. Cousins, too, never returned to the United States. Both artists should be better known in this country.

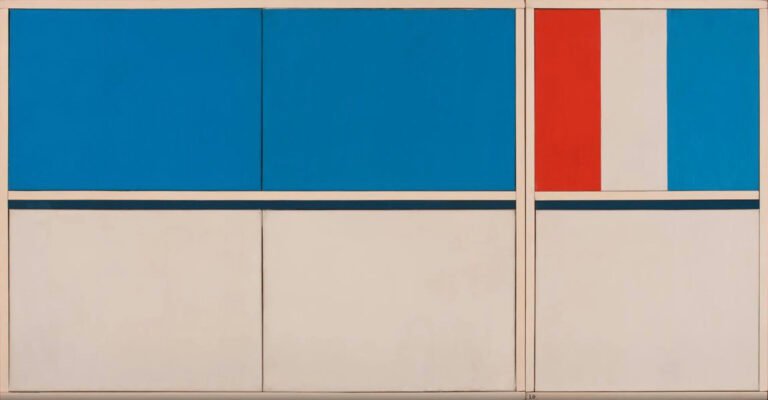

The exhibition goes a long way in representing the early work of artists I want to know more about. I was happy to see the paintings by James Bishop, Norman Bluhm, Ed Clark, Shirley Goldfarb, Carmen Herrera, and Shirley Jaffe from the first years of their careers. With more than 130 works by nearly 70 artists, including early geometric abstract paintings by the filmmaker Robert Breer and funky fiber pieces by Sheila Hicks, we can sense the vibrancy and openness of the Paris scene for Americans, and how much was happening, despite the lack of strong commercial support.

More than 400 servicemen went to Paris to study art on the G.I. Bill, but many women moved there as well, as did several Black artists, also benefitting from the G.I. Bill. Not surprisingly, the racial and gender diversity in Paris was not mirrored in the ascending New York art world.

I learned more about Ralph Coburn, a close friend of Ellsworth Kelly who introduced the latter to Jean Arp’s use of chance in composing his work; Kimber Smith, who rejected what Clement Greenberg characterized as the “huge painting” that many other American abstract artists would embrace; and the sculptor Claire Falkenstein, who said she was interested in “exploding the volume,” and is one of the most accomplished and experimental sculptors of her generation. Each of these artists deserves a longer and closer look.

The exhibition offers a lot to ponder. Why did Al Held take the hand out of his painting and commit himself to impeccable surfaces and illusionism? Was it internal forces or external pressures that caused him to change? Why aren’t Bishop’s early paintings, which anticipate Mary Heilmann’s seminal “RYB” works, better known? Why is Norman Bluhm still waiting to be rediscovered? Although he never severed his connection to Abstract Expressionism, as did many others, he went on to transform its vocabulary of gestures and drips into something that was voluptuously his own by the mid-1970s.

The outlier in this group is Peter Saul. His paintings don’t look like anyone else’s, either in Paris or New York, which is no small accomplishment. In his nascent vocabulary of cartoony, disembodied limbs, commercial goods, uniforms, bathtubs, animals, and weapons, we can discern his first connections between capitalist profit-making and the deep-seated roots of violence. Like Bishop, who was his roommate when they were students at Washington University, Saul kept the social aspect of the art world at a distance. Bricker Balken quotes him as saying: “The professional art world seemed like working in an office building.” It is good to remember that not everyone wanted to join the club.

This history — one in which New York is not the center of the art world — is important to remember. One response to being American that runs contrary to mainstream society is to not assimilate. That is what the Americans who moved to Paris had in common. Not all of them stayed true to that ideal. Bishop and Saul were among those who did.

Americans in Paris: Artists Working in Postwar France, 1946–1962 continues at the Grey Art Museum (18 Cooper Square, Noho, Manhattan) through July 20. The exhibition was curated by Lynn Gumpert and Debra Bricker Balken.